The University of Melbourne’s Wind Symphony is about to hit the road for its first-ever interstate tour – a three-city journey celebrating the vibrancy, versatility and musicality of wind ensemble performance in Australia today.

Led by Associate Professor Jaclyn Hartenberger, the 60-strong ensemble will perform in Melbourne, Brisbane and Sydney.

It’s more than just a talent flex, Hartenberger tells Limelight. It’s also an opportunity for student musicians to experience artistic exchange, professional development and be part of a major world premiere.

“We see it as a collaborative project,” Hartenberger explains. “In Brisbane, our students will rehearse and perform with students from Griffith University’s Queensland Conservatorium. Together, they’ll premiere a brand-new symphonic work by Australian composer Paul Dean.”

“That kind of collaboration gives them insight into how music is made in other institutions. It breaks the bubble of thinking your own training is the norm,” she adds. “Plus, some students from Singapore will be joining us for the Dean premiere, which will travel to Singapore later in the year.”

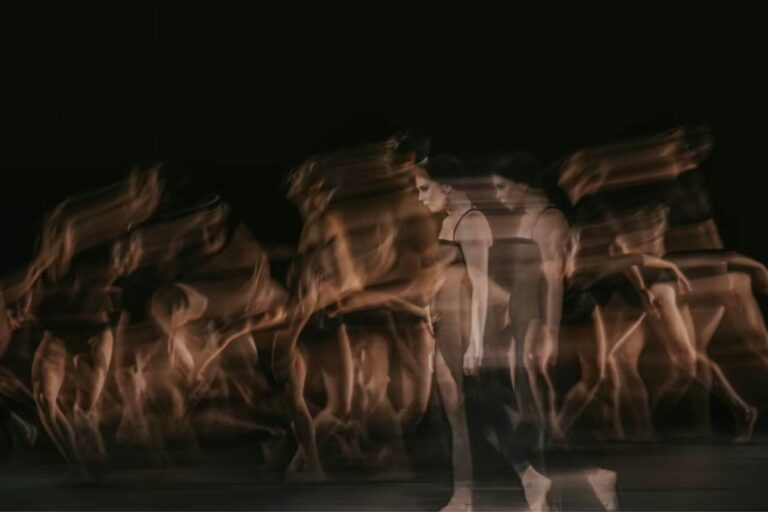

Jaclyn Hartenberger and the University of Melbourne’s Wind Symphony. Photo © Gregory Lorenzutti

The tour’s program is a showcase of wind ensemble repertoire, designed to demonstrate the artistic breadth and colour of this often-underappreciated format. From 20th-century master Paul Hindemith to rediscovered works by Australian composer Katherine ‘Kitty’ Parker (1886-1971), the program spans the serious, the lyrical and the little-known.

“The Parker pieces are part of a PhD research project of one of our students,” says Hartenberger. “She’s exploring Australian popular music from the late 1800s and early 1900s, when the town wind band was basically like a radio station. In those days, a popular song might be published in the newspaper as a piano score, and your local town band would bring it to life straight away.”

Also featured is Hun Tur, a work by composer and Melbourne Conservatorium Senior Lecturer Melody Eötvös, first commissioned for the University of Melbourne Symphony Orchestra’s 2023 international tour. Inspired by Eötvös’s Hungarian heritage, the work is steeped in rhythmic intensity and sonic colour.

Third-year student flautist Grace Gao, 20, is particularly looking forward to working on the world-premiere performance of Paul Dean’s Symphony No. 4 for Winds (Conservatorium Theatre, Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University on 21 August). She also loves the “jazzy feel” of US composer Kevin Day’s Concerto for Wind Ensemble, which is also on the program, a work made up of movements evocatively titled Flow, Riff, Vibe, Soul and Jam.

Jaclyn Hartenberger and the University of Melbourne’s Wind Symphony. Photo © Gregory Lorenzutti

“We’re sharing the stage with students from Griffith, so that’s exciting, and from what I’ve heard of the Paul Dean piece so far, I think it’s going to be really cool. It’s quite challenging,” says Gao. “I’ve studied the audio file we were sent but I’m very excited to hear what it really sounds like.”

Gao is hoping to continue her studies into an Honours year. “I really want to study with as many people as possible and gather different perspectives. I want to solidify my identity as a musician.”

She hopes to join a symphony orchestra in the future but that’s not the be-all, Gao says. “I’d like to be doing my own chamber projects and exploring wider material. One of the great things about being a wind player is that a lot of the music is comparatively new – composed in the last 50 years or so, and there’s more coming – especially from America which is a very distinct genre in itself. It’s not just orchestral pieces rewritten, because we do have some of those, yeah. They’re new and different.”

From Hartenberger’s standpoint, the tour offers a unique view into what it means to be a wind musician in the 21st century – and why wind playing, long overshadowed by string-dominated orchestras, is finally enjoying a moment.

“There’s something different about wind player training,” Hartenberger explains. “String players often focus on a very unified repertoire, but wind players are expected to be versatile across classical, jazz, funk, avant-garde and more. It creates incredibly flexible, multiskilled musicians.”

That versatility has found a perfect outlet in today’s industry demand. From film scores to pops orchestras and jazz orchestras, wind players are enjoying a creative boom. “There’s so much great music out there for wind players, and so many opportunities to perform.”

What’s more, wind ensembles offer a level of accessibility and innovation that large orchestras often struggle to match.

“The wind band is an incredibly agile format,” Hartenberger explains. “It’s more open to experimentation – the use of electronics, improvisation, mixed genres. It has the flexibility to evolve, and it allows more players to be involved without doubling parts. You can do so much creatively.”

Hartenberger sees the wind ensemble becoming a vital vehicle for documenting our times – a place for composers to respond to the world around them. “Music is such a powerful way to communicate how we feel about a moment,” she says. “Wind ensembles are commissioning more and more work that reflects now, and I think we’ll look back and see that wind bands were the ones telling the stories of this time.”

The University of Melbourne Wind Symphony plays Elizabeth Murdoch Hall, Melbourne Recital Centre (17 August); Conservatorium Theatre, Queensland Conservatorium, Brisbane (21 August); and Verbrugghen Hall, Sydney Conservatorium of Music (23 August).

Comments

Log in to start the conversation.