At the tender age of 63, the Czech composer Leoš Janáček fell head over heels for a woman he’d met on holiday. She was 40 years his junior, happily married with two children and never returned his rather obsessive affections.

Nevertheless, Janáček inundated Kamila Stösslová with letters and she became his muse for operas, masses, symphonies and song cycles – one of the most enduringly popular of which is the opera Katya Kabanova, published five years after their first encounter.

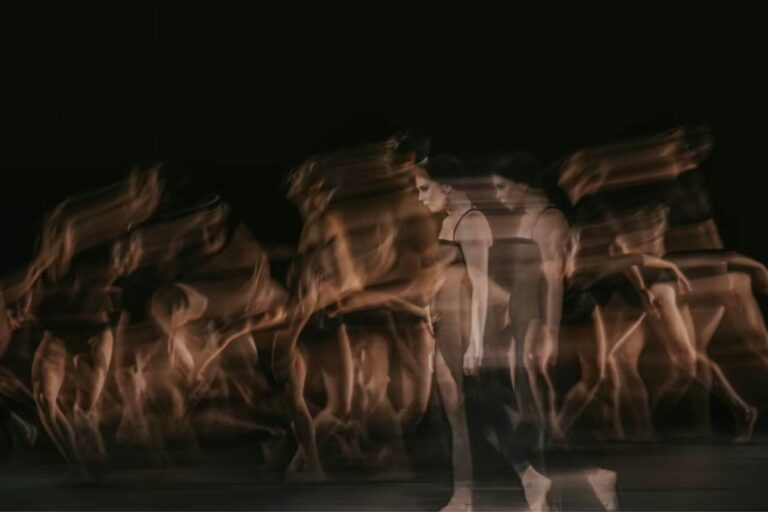

Victorian Opera’s hero image for Katya Kabanova. Photo supplied

Anyone can read into why the story appealed to him so much. An adaptation of the 1859 play The Storm by Alexander Ostrovsky, it centres a messy love triangle that favours the underdog. The titular Katya is trapped in an unhappy marriage with the weak-willed Tichon (and, by unwilling extension, with his bitter, overbearing mother). When Tichon leaves on business, Katya falls in love with Boris, who has loved her quietly through it all. As her husband returns and a storm begins to blow in, her guilt starts to consume her.

In Victorian Opera’s upcoming production of Katya Kabanova,...

Continue reading

Get unlimited digital access from $4 per month

Already a subscriber?

Log in

Comments

Log in to start the conversation.