Every cherished note seemed to creep into a silent cathedral during the intimate Introit opening of Verdi’s Requiem, performed by the Queensland Symphony Orchestra and the Brisbane Chamber Choir Collective.

It was a soft, contemplative introduction to Verdi’s epic, reflecting on mortality and spirituality before the sheer terror of Dies Irae (Day of Anger) ensued. More than 250 performers unleashed hell into the QPAC Concert Hall, as Italian conductor Umberto Clerici slashed his baton like Halloween‘s Michael Myers and the choristers bellowed the promise that the world would be reduced to ashes on the impending day of wrath.

Not your usual Friday night out, but one that will linger chillingly in the memory as one of the greatest musical spectacles I’ve experienced. Verdi’s Requiem is one of many musical settings of the traditional Roman Catholic Requiem Mass (Messa da Requiem), yet despite Verdi’s lack of religiosity, his operatic interpretation – laden with fire and brimstone – reigns supreme.

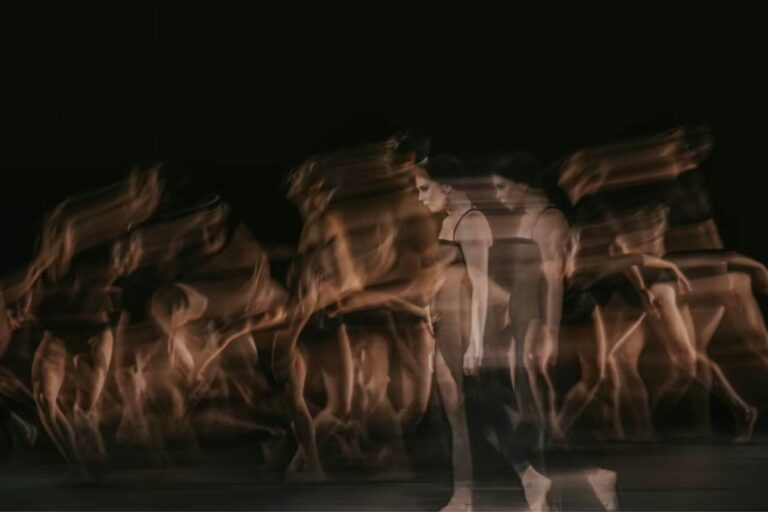

The QSO Verdi Requiem. Photo © Sam Muller

The monumental composition originated from the...

Continue reading

Get unlimited digital access from $4 per month

Already a subscriber?

Log in

Comments

Log in to start the conversation.