Art and politics sometimes make for uncomfortable bedfellows, but every now and then they come together in the complete package. About half an hour into our conversation I ask the great soprano Jessye Norman if she is still a Democrat? “Absolutely, God!” she exclaims. “With all that is going on on the other side, more loudly than ever. It’s truly frightening what could happen if we are not vigilant. It would be a tragedy for the world, and certainly a tragedy for the United States.”

“It’s truly frightening, what could happen, if we’re not vigilant. It would be a tragedy for the world“

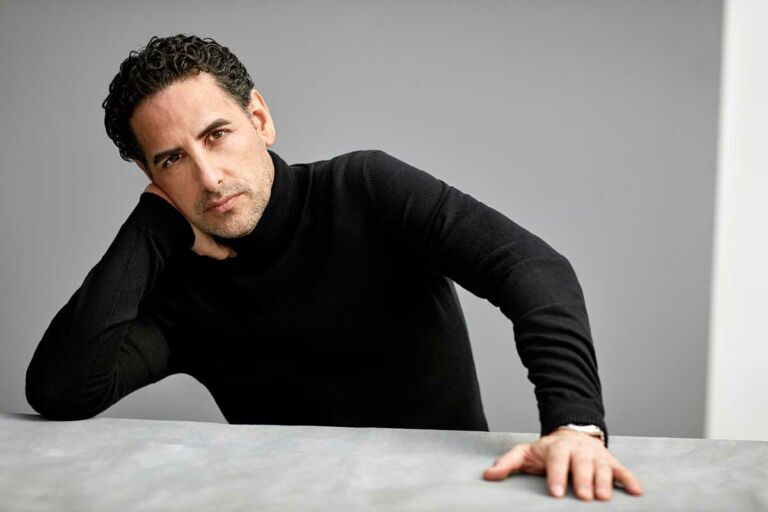

Soprano Jessye Norman.

Soprano Jessye Norman.

Direct, spontaneous statements have earned Norman a reputation for outspokenness and honesty, sometimes rare in a profession where people may feel a guarded approach oils the wheels that get you to the top. She can also be fearsomely determined – a handful, according to some – and I’ll admit to some trepidation prior to our encounter. The presence on the other end of the phone, however, is warm, friendly and relaxed, sympathising with me for having had to traipse into the office for a 7:30am interview. Over the following 40 minutes she’s candid and enlightening on a wide range of subjects, from music to race, from reality TV to education, as befits a singer who might just as easily have been a doctor, a teacher or even, I dare say, a formidable politician.

Jessye Mae Norman was born in Augusta, Georgia in September 1945, two weeks after Japan’s surrender ended her country’s involvement in the Second World War and a month before the formation of the United Nations. Both her parents were musical and the young Jessye found herself singing spirituals in the local Baptist choir by the age of four. “Singing excited me as a young girl simply because it was available,” she explains.

Classical music was ‘available’ too, and Norman would eagerly watch Toscanini’s NBC broadcasts. “I was five, but I understood what was happening. I didn’t know how to pronounce his name, but mother said it was important so therefore you had to watch. It wasn’t considered elitist. In the same way, nobody told me when I was ten and I happened upon the Metropolitan Opera broadcasts on a Saturday that I was supposed to know about opera. There was a man who told you what everybody was wearing and what the story was about. It didn’t occur to me that I needed to know Italian in order to appreciate it.”

Norman would be the first to lament the decline of classical music in mainstream media. “My goodness,” she exclaims. “Television used to be a form of education as well as entertainment. The Metropolitan opera isn’t shown nearly as often as it was when I was a part of the ensemble. People have decided reality shows are cheaper, so why have a bunch of people that have studied their crafts for 20 years on television?”

Growing up in a golden age for singing, Norman cites Sutherland, Leontyne Price and Robert Merrill as important voices. She mentions encountering the voice of Canadian tenor Jon Vickers as a special moment. “I thought it was one of the most extraordinary things I’d ever heard,” she says. “I shall never forget going to a performance, I guess I was in college at the time, and Jon Vickers was singing Fidelio. The first thing he says is ‘Gott! welch’ Dunkel hier!’ – Lord, how dark it is in this place. I sat straight up in my seat and said, ‘Who in the world is that man?’”

With Marilyn Horne at a Carnegie Hall master class, 2013

With Marilyn Horne at a Carnegie Hall master class, 2013

By coincidence, I have vivid memories as a young graduate of hearing Norman sing Das Lied von der Erde with Vickers at a BBC Prom in 1985. It was the first time I’d experienced an effect I have since come to regard as a benchmark for that handful of special performances, where a singer’s truthfulness and intensity makes the outside world close in like a collapsing telescope until it’s just them and me. Although it is not something she believes can be manufactured, that quality where a musician “captures” a listener is something Norman has experienced herself. “You couldn’t look away if Isaac Stern were playing the Bach Chaconne,” she admits. “How in the world do you get your fingers to crawl up and down the strings like that? You’ve got this bow in the other hand, and look how busy it is! It’s just amazing.”

But she can also be pragmatic about the attentivity of an audience. “Either they’re there to listen and enjoy, or they’re there for other reasons, which means they’re distracted. All you can do is present whatever it is you do, whether it’s solo dance or playing the Bach Chaconne, or singing Strauss songs. It is up to you to do your job, and I sincerely feel that if we do our jobs with enough passion and commitment, then the fact that audiences might be thinking about their grocery list or what they’re going to have for dinner, I think that goes away for a moment. I say this to students all the time. Don’t come on stage thinking, ‘Hmm, I’ll get through this tonight’. No, think ‘This is an opportunity,’ and just grab that opportunity.”

As a student herself, Norman is adamant she wasn’t special. Her mother was clearly an influence – her gentle admonition to “stand up straight and sing” became the title of Norman’s 2014 memoir – but it was a community of interested and encouraging people who made the difference to her and her contemporaries. “We were completely interchangeable,” she tells me, insisting she is not being in any way modest. “There were about five or six of us girls and one boy, Clyde, who had a wonderful soprano voice. If I couldn’t sing, then my friend Sabina would or Martha would. There was no reason for me to think my voice was any different from any of my friends.”

In fact, at that stage Norman was seriously considering medicine and had the maths and science credits to do so. “I didn’t see any clear path to make a living from singing because I was never paid,” she says with that typically rich laugh that punctuates a great deal of our conversation, “I mean, every now and then I was given a nice ice cream or something, but I realised that wasn’t the way to go if you wanted to pay your bills. No, I was very interested in medicine. But I think quite honestly, and when I say this now everybody laughs, I might have been the only person around me who thought I was going to medical school.”

“I might have been the only person around me who thought I was going to medical school“

Success in the Marian Anderson Vocal Competition led to a full scholarship at Washington’s Howard University and intensive vocal studies. She credits her singing teachers for never being bamboozled by her famously wide ranging soprano voice, capable of lyric or dramatic singing alike, but also strong in the mezzo register. “I wasn’t allowing myself to be called a certain type of soprano,” she explains. “At age 23, a person who was interviewing me tried to tie me down. ‘You were singing Medea, which has coloratura passages, but then you were singing this, which is very low,’ they said. ‘What kind of soprano are you anyway?’ I didn’t know what to say, but out of my mouth came the words: ‘I think that pigeonholes are rather more comfortable for pigeons.’ I thought that was pretty clever for a 23 year-old.”

Jessye Norman with Kurt Masur at the University of Michigan commencement, 1987

Jessye Norman with Kurt Masur at the University of Michigan commencement, 1987

It was wealthy American opera enthusiasts J. Ralph Corbett and his wife Patricia who gave Norman the chance to audition for work overseas. “Each year they would invite about 25 general directors from European houses to come on their dime to New York,” she explains. “For two weeks they would be taken to the theatre and concerts, but during the day they would have to sit and listen to American singers, and I was one of them. I sang Elisabeth’s second aria from Tannhaüser and the director of the opera house in Berlin, which at the time was the largest in Germany, asked me if I happened to know the rest of the opera. I said, ‘No, but I could learn it by next week.’ He said, ‘well, no, not quite so quick,’ and so, he invited me to make my debut in Berlin even though I was a student and I was still working on my Masters degree.”

Seldom-daunted, Norman studied German and conversational German for five months – “I thought it would be ridiculous for an American to sing a Wagner opera in Germany and not be able to communicate with my colleagues” – and headed for Berlin. In what she calls “a fantasy”, in the middle of the opera, the Intendant came up and offered her a contract. “I said, ‘Thank you, but I haven’t sung the third act.’ He said, ‘I heard you sing in New York, and I’ve heard your rehearsals – I think you’re doing just fine.’ It’s a ridiculously marvellous story, and completely true.”

Hailed as the greatest German soprano since Lotte Lehmann, role debuts followed thick and fast in all the major houses – Leonora in Fidelio, Aida at La Scala, Berlioz’s Dido, Purcell’s Dido, Sieglinde in Die Walküre, Ariadne… but Norman was always careful with her choices. “I’ve only sung the operas I really, really love,” she explains, declining to pick a favourite: “It would be like which of your children do you prefer? I couldn’t do that.” Furthermore, Norman has never been pushed into anything she didn’t want to do. “It doesn’t take very long, once you know me, to know that’s quite impossible,” she laughs. “I’ve certainly done things that were wrong-headed, but they were my decisions.”

The only role she’ll confess to having missed out on was the Countess in Richard Strauss’s Capriccio. “The last part is such a beautiful thing. There are about 11 minutes of incredible music when she’s trying to decide whether words or music are more important. It’s a wonderful thought, and it’s a wonderful discussion isn’t it?” And Jessye Norman? What does she reckon? “My goodness, I think that they have to go together. They’re of equal importance. Even in those operas where you sing ‘mai più’ 85 times!”

Although she has worked with all the great maestros, she won’t single out favourites, save to say that she has learned from simply being in rehearsals. “There are those conductors that are simply singing with you,” she says. “It’s such a difference from those who are glued to the page – or God forbid, with their eyes closed conducting from memory. That simply leaves you thinking, ‘Well, it looks like you’re in this on your own kid!’”

Nowadays, she’s the proud patron of the Jessye Norman School of the Arts in her hometown of Augusta – “it’s an incredible honour” – and she serves on the boards of Carnegie Hall and New York’s Public Library, as well as the Elton John AIDS Foundation and the Partnership for the Homeless. In fact Norman has always instinctively chosen to ‘give back’ at community level. In the 1980s, I recall seeing a plaque outside a youth centre at the top of London’s Edgeware Road saying that it had been opened by Jessye Norman. Working with less-advantaged kids has been a part of her life it would seem for decades.

Paris, July 14, 1989: Preparing to sing La Marseillaise for the bicentennial of the French Revolution

“I’ve never thought of it as something different, or even work at all, because you see my parents were involved in community service always, and so therefore their children were involved as well,” she explains. “I met these kids in London, and then asked to come and talk to them. It’s about wanting to help them understand their worth. Children can get lost so easily and they sometimes need just a little support. Maybe someone across the road says, ‘Oh, you really read that scripture beautifully in church the other day,’ and that’s all they need. Sometimes of course it’s much more complicated, but often it really is that easy. I’d say I believe in random acts of kindness.”

At the Jessye Norman School the kids study music, photography, drama and writing, as well as theatre work and management. “They’re middle school kids who come to us tuition free, which means I spend lots of time raising money,” she says, “but they are glorious and they are talented! They had their school closing last week and what did they do? They did The Wiz! They built the set, they built the costumes – you have to see our lion! – they rehearsed the music. They did it all. They were amazing.”

Of course race is still an issue, whether in America or Australia, and Norman, who says she “absolutely” has suffered herself in the past has long been an outspoken campaigner for tolerance. “Too often the idea is to pretend that racism isn’t pervasive in this world,” she declares. “But of course one suffers discrimination if you happen to be part of any minority, whether as a woman, or of African ancestry, or whatever. The problem is, we’re so busy seeing the things about each other that we think are different, we don’t realise that there are more things about us that are alike. And vocal chords are all the same colour. Interesting…”

And as far as young singers are concerned, Norman’s mantra is that being prepared is the best weapon. “Success comes when opportunity and preparation collide,” she says. “All you need is the opportunity to show what you can do.”

Receiving the National Medal of the Arts from Barack Obama in 2009

Receiving the National Medal of the Arts from Barack Obama in 2009

A professed Democrat from way back – one of her proudest moments was receiving the National Medal of the Arts from Barack Obama, a man she has spoken proudly of throughout his Presidency – she’s also a definite fan of Democratic hopeful Clinton. “Always have been,” she says. “Hillary’s first job as a law student was to go manage the Children’s Defence Fund and that’s one of the organisations that’s been very close to my heart forever. As a star pupil coming out of Yale, she could have taken some big, crazy corporate job I’m sure, but she decided she’d go and work for a not-for-profit organisation because of her Methodist faith and a feeling that one should go out and do good in the world. Think of the mountain of experience that she’s had? My goodness, there hasn’t been a person running for the Presidency with more experience in government than she’s had since John Quincy Adams, and that was a long time ago.”

“It behooves us to understand what the stakes are,” she continues. “This anger that the media wants to keep telling us is out there – people want change and all the rest of it – we’d better settle down and understand that change isn’t always good, it’s just change. What we need at the helm of the free world is a person of some humility, a great deal of experience and, please, less bravura.”

Supposing ‘bravura’ to mean Donald Trump, I tentatively enquire whether she’s ever met the man? “Yes I have… I’m afraid,” she laughs. “I think that rather covers it.” But she has some serious points to make, and in finest Jessye Norman style, she makes them: “It’s unbelievable what is happening,” she says. “No one in this country can explain the craze for someone who is actually a television personality. He doesn’t have the faintest idea! I mean, to give a public foreign policy speech and to mispronounce Tanzania because he doesn’t know any better – this is not possible! To say you have had experience dealing with the former Soviet Union because you held a beauty contest there? Are we kidding? I’ve sung numerous times in Moscow and St. Petersburg, but does that make me qualified to run for the Presidency? I don’t think so.”

Such spirit is typical of this remarkable and engaging woman. It’s been an absolute pleasure, and as we finish up I can’t resist a sneaking thought that if anything were to happen to Hillary, come November Jessye Norman would make a formidable opponent for ‘The Donald’.

Comments

Log in to start the conversation.