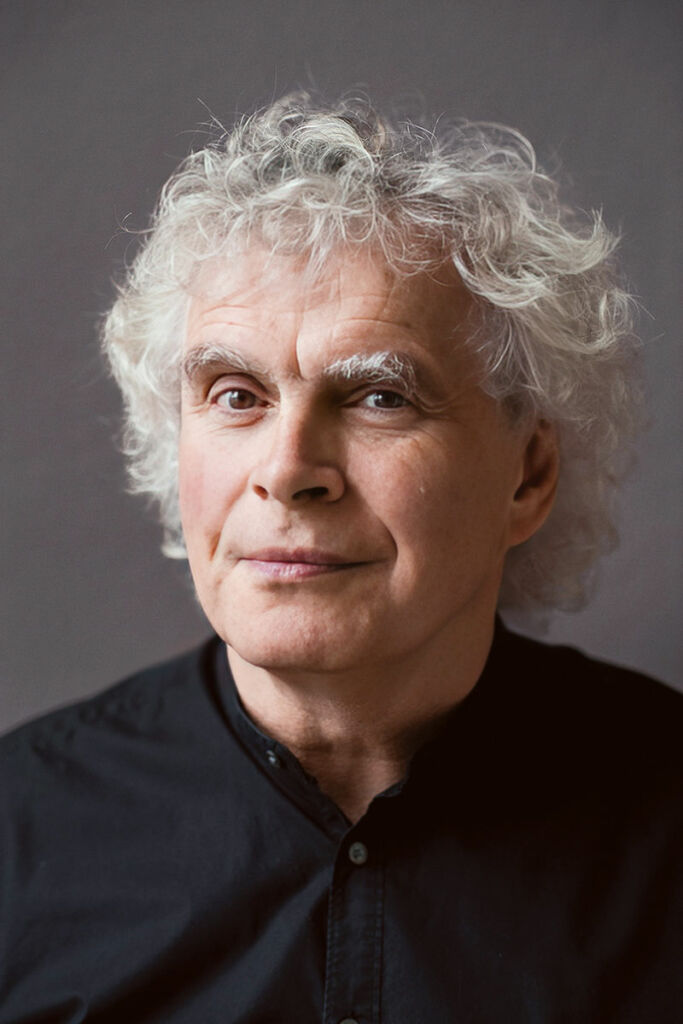

Over coffee at his local London café, Sir Simon Rattle talks to Clive Paget about everything from Bruckner to Brexit, as well as music education and the London Symphony Orchestra’s forthcoming tour of Australia.

If, like me, your concertgoing life began in England around 1980, you will likely have grown up with Simon Rattle. Appointed Principal Conductor and Artistic Adviser to the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra at the age of 25, every other month it seemed the Liverpool-born wunderkind with the mop of curly hair achieved something of note. Whether it was his bold, innovative programming, or earth-shattering performances, Birmingham was the place to be. His 18-year stint in Britain’s second largest city was a mark of the reciprocal respect and enthusiasm that blossomed between the CBSO players and their dynamic and refreshingly collegiate leader.

In many ways, Rattle – now Sir Simon Rattle – hasn’t changed a bit.

The trademark locks may now be snowy white, but the sparkle, the brilliance and the gentle, self-deprecating humour remain the same.

It may be a cold and drizzly January morning in London, but an hour in the conductor’s bustling local café flies by as we talk about everything from Bruckner to Brexit, as well as the repertoire he’s bringing to Australia as part of the London Symphony Orchestra’s upcoming three-city tour.

Chatting about those early days in Birmingham, Rattle remembers some of the legends he was required to take in his stride. “One of the first concerts was with [Russian pianist] Emil Gilels,” he recalls. “I must have thought, ‘Oh, well, I suppose this is what you do.’ I mean, Gilels was drunk, and [Russian-born American violinist Nathan] Milstein had so many strange twitches, but then you remember these people and realise what a privilege it was.”

Canadian tenor Jon Vickers was another artist he never expected to work with. It was a 1985 BBC Proms performance of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde and Jessye Norman was the other soloist. Coincidentally, it was the first time I saw Rattle conduct live. “Everybody had said, ‘Oh, Jon Vickers, he’s a great singer, but he’s a really difficult person – do be careful,’” he tells me. “When I went to see him at the flat where he was staying, he opened the door, gave me a hug, and said, ‘Oh, look Simon, I mean, I love this piece, but I find it incredibly difficult. I’ll do anything you ask me if I can do it, but sometimes you might have to help me a bit.’”

“I thought, ‘I love this person’,” Rattle laughs. “On the other hand, Jessye, who I absolutely adored, went full diva when she saw the filming. I still have the letter from her agent, saying, ‘Ms. Norman has watched the filming, and it seems that the director believes that the principal flute or the principal oboe could be as important as she is.’ I was expecting Jessye to be easy, and she wasn’t, and I was expecting Vickers to be impossible – though I do remember him drinking an entire bottle of cough mixture just before he came on.”

In those early days, Rattle says, people were normally very kind. “I had an enormous amount to learn and there were people who really [helped],” he explains. “A lot of the piano concerto repertoire, I learned profoundly from Alfred Brendel – ‘This is what you need to do; try this.’ We all need it, because when you start conducting, you may have an instinct for it, but there are so many things you just don’t know.”

That is one of the reasons that Rattle tries to mentor people whenever he can. “They just need someone on the end of a phone, going, ‘Simon, what the hell do I do?’,” he says. “It can be about repertoire, or career, or simply how do I get round this corner – a female conductor [asking] how to deal with an entire bassoon section who are aggressively on their phones for the entire rehearsal so as not to have to look at her. We all have problems, and we all need our friends.”

It’s the week before his 68th birthday and Rattle is relaxed, though politely concerned that I might find the café too noisy. We’re just around the corner from his London apartment, and in the opposite corner, his wife, Czech mezzo-soprano Magdalena Kožená, is having an impromptu meeting with her agent. Rattle is clearly a regular, pausing to pass the time of day with staff members. “You’re a musician, aren’t you?” remarks one of them. “Yes,” comes the modest reply from a man who must have conducted every major orchestra on the planet.

Given the many highlights of a nearly 50-year professional career, I’m curious: was he ever nervous? And is he ever nervous now? “It depends. Certain great pieces can be a huge deal,” he admits. “Before my first [concerts] in Vienna, I thought I would never get out of the hotel bathroom, I was so sick. The principal cellist came to me in the interval and said, ‘Oh, this is so much fun, I feel like we’re all loving it.’ And I said, ‘Really, I’m so nervous!’ He said, ‘Don’t you be nervous, we invited you to come – we should be nervous!’ I thought that was incredibly generous.”

Rattle’s break came early. In 1974, he became the 19-year-old Assistant Conductor to Paavo Berglund at the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra. The following year he joined the Glyndebourne music staff, and in 1976 he led his first BBC Prom conducting the London Sinfonietta in a program that included thorny music by Harrison Birtwistle and Schoenberg’s First Chamber Symphony. The Birmingham appointment came in 1980. Over the next 18 years, he notched up one of the most eclectic and wide-ranging discographies in the catalogue. He went on to spend 19 years as Claudio Abbado’s successor at the Berlin Philharmonic, followed now by five years helming the London Symphony Orchestra. He takes up his new appointment as Chief Conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra at the start of the 2023–24 season.

Given his diverse repertoire, there are still plenty of pieces that fire him up. “Everything gives you an adrenaline buzz, but it’s the gigantic mountains, like the Matthew Passion, for instance, and before Beethoven’s Ninth,” he says.

“I think Mahler Seven is one of those in many ways,” he adds, referring to a work considered by some to be the Cinderella among the composer’s output. Australian audiences will get to hear it on the LSO tour. “The finale is this extraordinary construction that keeps winding up and winding down. It’s hard to know quite what he was trying to do, and I find that fascinating. The writer Paul Griffiths has this wonderful picture, which helped, that this is not a journey from night into day, it’s a journey from night into the false day of a theatre, where every opera Mahler was conducting was bouncing around in his head. They’re all jostling for attention. You can hear bits of Boris Godunov, you can hear bits of Seraglio, you can hear all kinds of operas.”

Rattle finds images – even colours or phrases – useful in the rehearsal room as well. “Often it can be a picture that helps, and sometimes,” he smiles, sipping his latte with evident relish, “it can be a coffee.”

Ideas can even help an orchestra in performance. “It’s always a drama – it’s always some kind of story,” he says. “This [he says, waving an arm] is a certain amount of use, but a lot is what you can pull out of here [tapping his head].”

In the weeks leading up to our meeting, I’ve watched Rattle at work, conducting the LSO in music by some of his ‘special’ composers. There was a thrillingly insightful concert performance of Janáček’s Káťa Kabanová and a brilliantly devised journey through the life of Stravinsky by way of his rarely played orchestral miniatures. In one of the finest performances of Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony I’ve ever heard, Rattle conducted a new Urtext version of the score from memory. It’s the focus of the LSO’s NSW bonus concert, and Sydneysiders are in for a treat!

“The thing that is clearest about the new edition is where there are tempo changes and where there aren’t,” Rattle explains. “When you have a score, which is entirely without everybody else’s ideas, you think, ‘Oh, my God, it’s all one pulse, it’s basically all one pulse.’”

But what is it about the work that draws him back? “I suppose, it’s the singing . . . the lyricism,” he reflects. “Somehow, it’s the closest thing to enormous Schubert. If you listen to the G-major String Quartet, you realise this symphony is its younger brother.”

Rattle recalls happy hours spent talking to the late Nikolaus Harnoncourt and readily shares some of his colleague’s thoughts on the Seventh Symphony. “What is it about orchestras when they see the name Bruckner,” he relates, in his best Austrian accent. “They look at music which is so Classical, however Romantic the harmony, and they all go ‘Bleurgh!’ – it’s absolutely true! Why do we play this fat sound without phrasing? Why, when he says at the end of the first movement, ‘Gradually get faster and faster until the end’, does everybody get slower? Why don’t we do what we would with any other music, and just do what he says?”

Harnoncourt’s theory, and Rattle agrees, was that during the Second World War in Austria and Germany, Bruckner interpretations came to express the horror of what they were living through. “Somehow it became filled with steroids – it just got slower and slower, and fatter and fatter,” he explains. “If one goes back to early performances, it’s a very different style – Schubert is still in the frame. That’s been a fascinating journey to go through.”

Watching Rattle on the podium today, his modest physicality oozes intent. The way he shapes a phrase, the way he ensures the orchestra slips easily from subject to subject, it’s a masterclass in clarity and imaginative gesture.

Legs apart, occasionally urgent, in the Bruckner his face conveys varying degrees of desperation. By way of contrast, his expression is one of tender radiance during a performance of Sibelius’s The Oceanides – another composer with whom Rattle has a long-standing affinity. When I ask if his conducting technique has changed over the years, he’s typically self-effacing. “Yeah. I’m sure it’s got less worse.”

“Look, some people have the most incredibly natural techniques, and then there are the rest of us who make it up as we go along,” he continues. “Some can get whatever they want with a stick, but I’m not one of those; although I can make an awful lot of things work. But sometimes it is better if the orchestra can get it from within, from listening, and from what you’re doing, rather than by reacting against the beat.”

As a young conductor, Rattle preferred watching Kubelík over Maazel, even though Maazel’s stick technique was immaculate. “Kubelík was one of the most ungainly conductors,” he recalls, “but my experience as a 15-year-old, when he came with the Bayerischer Rundfunk to Liverpool and played Beethoven Nine, was one of those changing-of-life moments. That close relationship between a conductor and orchestra . . . I never forgot it.”

Although he started out on piano and violin, graduating to playing percussion in the Merseyside Youth Orchestra, Rattle knew he wanted to be a conductor early on. Around the age of 12, he heard a performance of Mahler’s mighty Resurrection Symphony conducted by George Hurst. “That was the fall on the road to Damascus – unforgettable,” he says. “I thought, ‘You don’t make the music, but the electricity flows through you to the orchestra and to the audience. This, somehow, I must do.’”

Mahler’s Second Symphony has followed Rattle across the decades. As a student at London’s Royal Academy of Music, he organised and led his first performance. “It was a very strong orchestral training program but there were all kinds of things – contemporary music, Bruckner, Mahler – that they felt was beyond us,” he explains. “We all wanted to play this music and so we had to get it together ourselves. When I think what I did there: Mahler, Messiaen’s Et exspecto resurrectionem mortuorum . . . I remember persuading publishers to let me have the parts for either nothing or a fiver and I’d say, ‘Look, I’ll bring them back Monday morning.’”

Janáček is another composer who overwhelmed Rattle after experiencing The Cunning Little Vixen as a student. “This piece made me into an opera conductor,” he says. “It was Steuart Bedford conducting – I was in the pit. I realised, ‘Oh, yes. This is what I want in my life,’ never thinking that 40 years later I’d be living with someone [Kožená] who had lived round the corner from Janáček and walking in the forest called “The Cunning Little Vixen Forest”.

One of my own seminal musical experiences was hearing Rattle conduct the work at Covent Garden in 1990 – his Royal Opera House debut and coincidentally that of his son, Sacha, now a professional clarinettist, who sang one of the fox cubs. “Of course, it changes your life,” he agrees. “There were certain things that were obvious to me. As Haydn would always be there in my life, so would Janáček.”

Few senior conductors today have championed Haydn like Rattle, so what resonates there? “He’s the person I’d most like to bring here and have a coffee with,” he replies. “I just think, the best company, the best tempered, and highly intelligent – not on the level of a Mozart, who I think would be terrifying to sit opposite, but simply the most civilised and thoughtful [man], who made music because it was needed.”

Rattle also has a richly deserved reputation for championing contemporary music. One of his closest musical relationships is undoubtedly with John Adams, whose Harmonielehre is part of the LSO’s Australian program. The two men are now longstanding friends. “When John’s music came out, a lot of the contemporary music world was completely horrified,” Rattle recalls. “About three years ago, we went to Munich with the LSO and in the second half we played Harmonielehre. After the first movement, the audience cheered. These same people 20 years ago would have booed or walked out.”

When it comes to new music, Rattle has always preferred to be a broad church. “Sometimes I did programs with Elliott Carter and John’s music together, because I knew it would piss both of them off,” he laughs. “I think the best music of Elliott Carter is so beautiful, and basically everything by John is so beautiful. They could not be more different, but they belong in the same boat. Two great American composers.”

As a child, Rattle’s father was a keen amateur jazz musician, and so he grew up with an appreciation of the kind of harmonic structures Adams sometimes employs. “John is not only about the detail, he’s about this extraordinary depth of feeling,” he says. “I remember when we recorded The Gospel According to the Other Mary, I was listening [to the playback] and there was this point where I realised my score at the end of the first part was half-destroyed, because I was weeping onto the page.”

Education is another issue, and one of increasing concern. Rattle grew up at a time when youth orchestras were flourishing and most children had access to, or financial assistance with access to music. These days it’s very different. “In this country, provision is very patchy – certain areas have removed all the peripatetic music teachers,” he says. “The worry is that it becomes once again the province of the middle class and above. We were a middle-class family, but my parents could not have afforded the lessons I had. I got a scholarship, thank God. What’s interesting is that now orchestras and opera companies have stepped up to the plate, going into schools to provide other musical experiences. For more than 20 years, the LSO has been going into the 10 poorest boroughs in East London and spreading music.”

Rattle finds the current round of arts cuts – another topic that will surely resonate with Australians – equally troubling. “I wish the phrase ‘cultural vandalism’ wasn’t so overused, because you need to save it for a moment like this,” he says. “Obviously no one who has any idea about what it is to put on a concert is making these decisions. But the Conservative Party has been taken over by the kind of people who, if they started talking to you at a party, you would find a reason to edge away from.”

And don’t get him talking about Brexit, something he calls “the most egregious act of self-harm” inflicted on any country in the modern age. “Brexit has made everybody’s life much harder,” he confirms. “Weirdly, touring to Australia – although it’s incredibly expensive and we are using [local] percussion instruments, because we can’t afford the pallets to take all those marimbas, etcetera, etcetera – in some ways is less complicated than touring to Europe.”

Two years ago, Rattle, who has lived in Berlin for many years, took German citizenship. “I resisted it for a long time,” he explains, “but there came a point where I realised that this is absolutely necessary for my children’s sake. With German passports they can travel where they need and do things in Europe. I’m sure, in their lifetime if not in mine, we will be back in Europe, but probably never again with the kind of conditions we had before.”

Indeed, Rattle’s decision to take the Munich job was partly to allow him to spend more time with a young family that includes a 17-, a 14- and an eight-year-old. However, later this year he also becomes the LSO’s Conductor Emeritus, so he clearly still has plenty of plans for London.

“Look, I adore these people. I just love them to pieces,” he says. “I will keep coming [back to London] as long as I can still raise my right arm, quite honestly. I’ll be with them a month or six weeks each year. For instance, each year we’re recording a Janáček opera. After the Vixen, now it’s Káťa, next year it’s Jenůfa, then it’s Brouček. I would never want to lose touch with them.”

Meanwhile, he’s already looking forward to Australia. “I loved doing the Australian World Orchestra [in 2018], I adored it,” he says. “And it was great to take everybody there in summer, although Magdalena said, ‘I didn’t realise it was going to be so f**king freezing.’ But I would hope to have another AWO experience.”

So much, then, for suggestions that this might be his last trip Down Under. “All kinds of people have told me, ‘Oh, so you’re retiring?’,” he laughs. “I say, ‘No, I’m a conductor – at 70, we start to know what we’re doing!’”

Sir Simon Rattle and the London Symphony Orchestra perform at QPAC, Brisbane, 28–29 April, Sydney Opera House, 1–3 May, and Arts Centre Melbourne, 5–6 May.

Comments

Log in to start the conversation.