Sydney Symphony Orchestra proved itself to be a first-class interpreter of Dmitri Shostakovich’s symphonies under the stewardship of its then Chief Conductor Vladimir Ashkenazy in the last decade, and this latest performance with Principal Guest Conductor Sir Donald Runnicles confirms it.

The performance of the mighty Fifth Symphony was compelling from the celebrated opening in the cellos and basses, the translucent floating strings like lofty clouds, and the woodwinds – first flute, then oboe followed by clarinet and bassoon – each adding subtle splashes of colour.

Runnicles allowed it plenty of space but ensured that the momentum built as horns, piano and trumpets added their muscle as the menacing march, with trombones, tuba and percussion all came to the crashing climax, giving way to the lovely consoling melody in the violins with its gently rocking harp accompaniment.

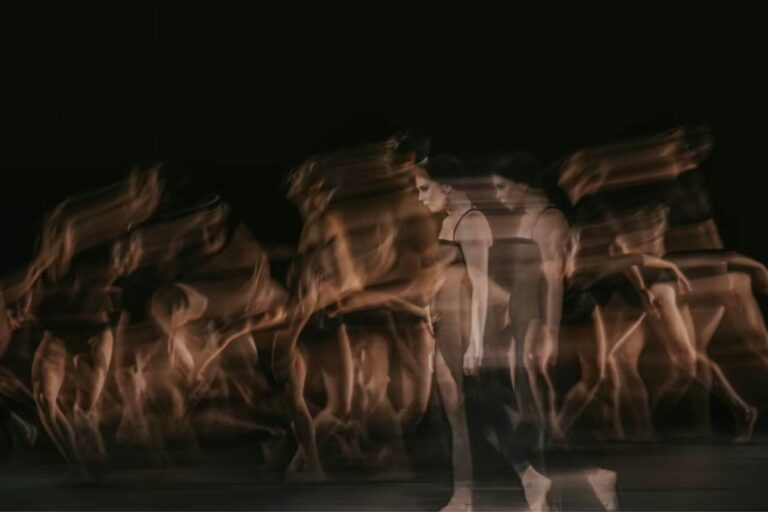

Sir Donald Runnicles conducts the SSO in Shostakovich’s Fifth Symhony. Photo © Craig Abercrombie/Sydney Symphony Orchestra

The work has remained popular since its premiere in 1937 put Shostakovich back in favour with the Stalinist elite after his opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk,...

Continue reading

Get unlimited digital access from $4 per month

Already a subscriber?

Log in

Comments

Log in to start the conversation.