One of the world’s finest horn players, Stefan Dohr, joins the Sydney Symphony Orchestra for two programs in August.

Here, Dohr discusses when he first fell in love with his instrument, his rapid rise to stardom, and what makes the music of Richard Strauss and Benjamin Britten so fascinating.

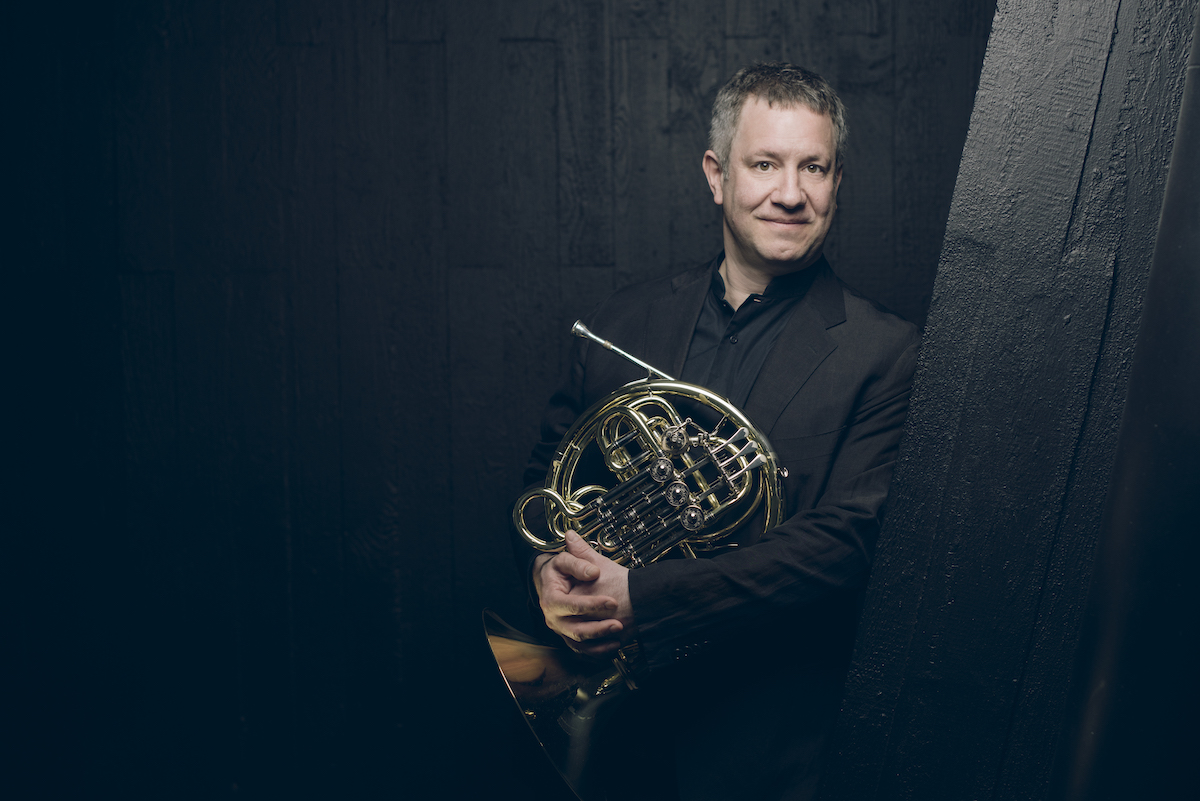

Stefan Dohr. Photo supplied

Proclaimed as the “king of his instrument”, Stefan Dohr is undoubtedly one of the world’s greatest horn players.

Currently Principal Horn of the Berlin Philharmonic, Dohr was appointed Principal Horn of the Frankfurt Opera at the age of 19. In the decades since, he has ascended to the pinnacle of the classical world: a valued orchestral colleague; an inspiring chamber musician, and a sought-after soloist with many of the world’s great orchestras.

In August, Sydneysiders will finally get their opportunity to experience the full breadth of Dohr’s artistry when he performs with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra in two different – though intriguingly connected – programs.

In three performances at the Sydney Opera House, Dohr will star in Richard Strauss’s Second Horn Concerto, a famously virtuosic work that places huge demands on the soloist.

That concert also features Antonin Dvořák’s deeply Romantic Seventh Symphony, counted among his greatest works, alongside Zoltán Kodály’s joyful, folk-infused Dances of Galanta, all led by conductor Ola Rudner – familiar to Australians from his time as Chief Conductor of the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra, and the many acclaimed ABC Classic recordings that resulted from that partnership.

The second concert has been curated by the Orchestra’s Concertmaster Andrew Haveron and will see Dohr perform Benjamin Britten’s Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings alongside Haveron and tenor Andrew Goodwin, coupled with Britten’s Prelude and Fugue for 18 Solo Strings and Rudolf Barshai’s ingenious chamber orchestra arrangement of Shostakovich’s String Quartet No. 10.

This second concert will be performed at the City Recital Hall.

The making of a musician

Stefan Dohr. Photo © Simon Pauly

Perhaps the most remarkable part about Dohr’s career is that it began comparatively late.

Dohr’s mother was a piano teacher and director of a music school in Essen, in the western part of Germany, and was eager for her three sons to learn an instrument. So she did what musical families have been doing for generations, and built her own string trio – handing out a cello, viola and violin to her boys, with Stefan on viola.

Before long, though, Stefan was taken to a performance by the great German horn player Hermann Baumann, and he was completely hooked.

Dohr smiles recalling that moment. “Hermann Baumann lived actually in the same part of Essen where I lived. When I was eight or nine I went to a concert that he gave for horn and organ, and I said, ‘Oh, that sounds much better than my viola playing’.

“And then my mother took me on to a horn teacher, and that was quite successful.”

That might go down as one of the great understatements, considering it only took Dohr 10 years to go from his first tentative notes on the instrument to being Principal of Frankfurt Opera. Though Dohr admits he was thrown in the deep end when he joined: Frankfurt is famous for its brisk repertory seasons, powering through lots of operas with precious little rehearsal time.

Dohr found himself having to sight-read everything, often not hearing them with a full orchestra until opening night. On top of that, the orchestra performed a dozen or so orchestral concerts every year, with barely any time to draw breath.

“It was quite scary,” recalls Dohr. “Luckily, I had a very nice horn section that helped me through.”

Playing “at the edge of the possible”

One piece that Dohr didn’t encounter in his Frankfurt years was the Second Horn Concerto by Richard Strauss.

Strauss wrote two concertos for horn: the first dates from 1883, while the fledgling composer was still a philosophy student at Munich University.

That piece is infamous among horn players, says Dohr with a laugh. “Auditions in Germany, usually it’s the First Concerto of Richard Strauss, and one of the Mozart concertos. If you wake me up in the middle of the night, I can play it.”

The second wasn’t written until 60 years later, in the great flurry of creativity that marked the final few years of Strauss’s life, which produced among other works his Oboe Concerto, Metamorphosen for strings, and the sublime Four Last Songs.

The horn concerto has since found a place among the most-performed and recorded works in the repertoire, chiefly because it is so challenging: the best players all want to prove themselves, and this is the ultimate yardstick.

Both works are hugely influenced by Strauss’s father Franz, who was a horn player of great renown in the late 19th century. A member of the orchestra of the Bavarian Court Opera for 42 years, he led the horn section in the premieres of Wagner’s grand operas Tristan und Isolde, Das Rheingold and Die Walküre, and was invited to Bayreuth to play in the premiere of Parsifal, performing the demanding horn solos in those works. All this despite his own dislike for Wagner’s music; the composer once famously said, “Strauss is a detestable fellow but when he blows his horn one cannot sulk with him.”

Dohr believes it is Richard’s intimate knowledge of the horn, though his father, that makes his Second Concerto – and many horn parts in his other works – so demanding to play.

“He did absolutely understand the instrument – that is the problem,” says Dohr with a wry laugh. “He knew exactly what is possible. The symphonic poems – Symphonia Domestica, Alpensinfonie, Heldenleben – they are all demanding. He really composed to the edge of what was possible.

“But the whole piece is actually quite joyful. I have always the feeling that people enjoy it very much, especially at the last movement.”

One of the enduring curiosities about this work is its bucolic and breezy tone, given it was written in 1943 – not just an era when music was increasingly dominated by Modernism, but also a time when Austria had been annexed by the Nazis. The horrors of war would touch the Strauss family directly: his daughter-in-law, Alice, was Jewish, and before the war was over 26 of Alice’s family would be killed by the Nazis.

Yet despite all that, Dohr says the concerto belongs very much to the Romantic tradition and even earlier. “It should have been terrifying time, but I actually don’t hear that at all. You hear Mozart, you hear Schumann – you have a lot of things, but you don’t hear any contemporary music at all in it.”

Intriguingly, the Strauss concerto was written in the same year as Benjamin Britten’s Serenade, the two pieces providing a fascinating snapshot of the world of music in the mid-20th century.

“They are the best two pieces for the horn in the first half of that century,” says Dohr. “But they are so different also from each other.”

“In the Strauss you can hear it is coming from this Classical-Romantic repertoire and sound. But Britten really used the instrument in so many different colours in these little pieces. And this is really fascinating.”

As well as being linked by their year of composition, Britten’s work was also inspired by a virtuoso horn player: the English player Dennis Brain, for whom it was written and who gave the premiere alongside Britten’s partner, tenor Peter Pears.

“The unique combination with the tenor, the horn and string orchestra – it gives it a very different space,” says Dohr, when asked what he thinks set the Britten apart. “All these movements are so special. They each have their own sound, and the way he creates them is so wonderful.

“Most of the time I don’t even play together with the singer. It’s like we are in parallel universes, but the combination with the strings and all those different and yeah, so many different colours.”

What a tremendous opportunity to experience all the colours this instrument has to offer, and in the expert hands of perhaps the world’s finest soloist, together with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra.

Stefan Dohr performs Richard Strauss’s Horn Concerto No. 2 from 18–20 August at Sydney Opera House, then Britten’s Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings in one special performance at City Recital Hall, 24 August. Tickets available from the Sydney Symphony Orchestra’s website.

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.