The program essay for Bell Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream seems keen to hose down any expectation we might have that the Bard’s best known and most performed comedy is, in fact, meant to be funny.

Shakespeare, notes self-confessed “theatre nut” Andy McLean, wrote the play in a period of “bad harvests, food riots, poverty and malnutrition … Child mortality was perilously high … England was a paranoid police state where all sorts of imaginative forms of torture and execution were dished out.”

For two-thirds of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, McLean writes, “most of the lead characters are unhappy.” Therefore, he concludes, the play “is more a black comedy than a golden idyll.”

I don’t doubt that life in Shakespeare’s England was pretty bloody miserable at times. But to allow a production to get bogged down in it strikes me as a bit wrong-headed. You can just as easily make the argument that the darkest times fuel the most anarchically funny responses.

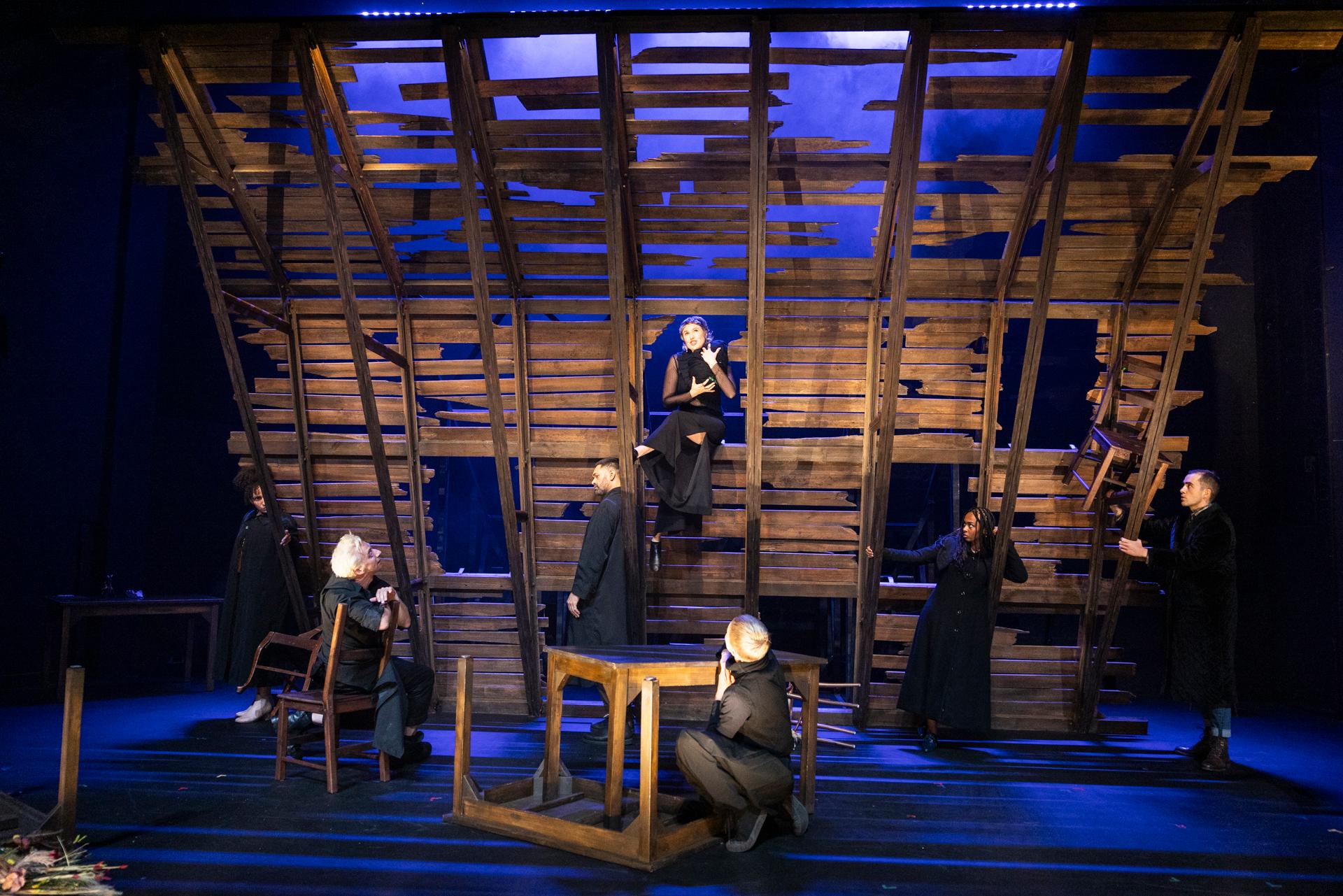

Bell Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Photo © Brett Boardman

Artistic Director Peter Evans’s production is something of a throwback to his condensed adaptation, The Dream, staged in 2014 for the company’s 25th anniversary season. It used the same Teresa Negroponte-designed set we see here, a storm-ripped shed roof tilted to vertical. Costumes are arranged in racks, side of stage.

Evans had a wonderful team of actors at his disposal back then, including top-shelf comic actors Julie Forsyth and Richard Piper. This staging features a relatively inexperienced cast (the veteran here is Richard Pyros; a spiky, post-punk Oberon) who seem reluctant to exploit their characters’ potential for laughs.

The result is a Dream that seems several shades more muted than its predecessor – an impression heightened by moody lighting (a Benjamin Cisterne design), wintry clothing (Negroponte) and Max Lyandvert’s unsettling electronic score.

Richard Pyros and Ella Prince in Bell Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Photo © Brett Boardman

In what is a physical, fast-moving staging (actors clamber up the set and pop in and out of its various apertures), Ella Prince makes a strong impression as Puck. So does Imogen Sage’s lithe Titania. Ahunim Abebe (Hermia) and Isabel Burton (Helena) imbue the roles with a solid sense of emotional truth but seldom are we permitted to laugh at them. Perhaps, things will loosen up as A Midsummer Night’s Dream tours the country (until late June) and the actors allow themselves to have some fun at their characters’ expense.

Laurence Young (Lysander) and Mike Howlett (Demetrius) aren’t strongly differentiated (justifiable, you might argue), with each as bland as the other. At the point where Hermia and Helena ready to trade blows, Evans leaves them sitting like a pair of pot plants. For a scene like that to really fly, everyone on stage has to be working for it.

The mechanicals aren’t strongly defined as comic personalities, either. Nor is there much interpersonal stuff bubbling away under their efforts to present Pyramus and Thisbe, which falls a bit flat despite an amusing wrestle with a late-appearing and very long sword.

Matu Ngaropo’s is probably the most reserved reading of Bottom I’ve seen to date. It’s an intriguing choice, but one that robs the play of the belly laughs that flow from his bombast. Post-transformation, any suggestion of interspecies coupling is downplayed to nothing. Bawdiness and belly laughter have no place here.

Bell Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream plays at the Sydney Opera House until 30 March. The production tours nationally until 29 June.

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.